Why Sicilian gesture is a real language

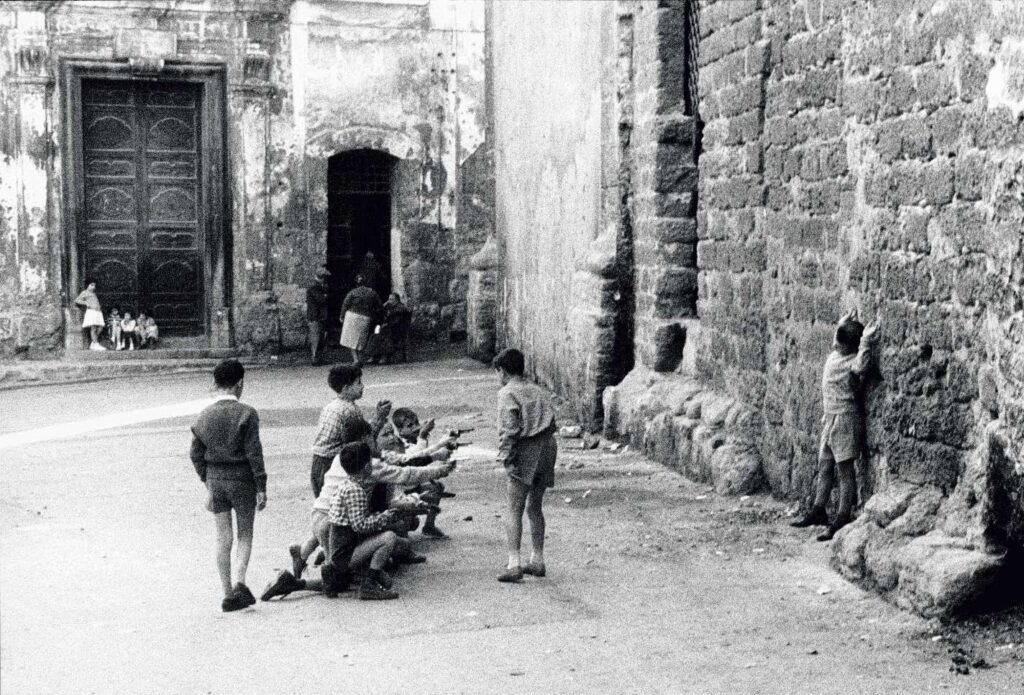

Paulo Coelho wrote that “every gesture made by a human being is sacred and full of consequences”. The Brazilian writer’s definition is full of lyricism and well suited to the nature of the Sicilian people, well-known for their many nonverbal expressions. From the smorfia (grimace) linked to the card games to the angry faces (with the hand between teeth) shown by Sicilian mothers when reproaching children after the umpteenth mischief, there are many expressions that accompany our daily life and make us recognizable to the curious foreigners’ eyes. However, we would risk being mistaken if we were to consider these gestures as simple and colorful habits, or even as a folkloric exhibit. In Sicily, gestures are the symbol of an art that has its roots in ancient times and that, over time, has ended up forming a literary and very personal language, a deep and essential nourishment of our rich theatrical production. It is not by chance that Giuseppe Pitrè, with his usual foresight, had already highlighted its importance in decades of research.

Thus, among the 25 volumes within his majestic collection Library of Sicilian Popular Traditions the last one is titled Sicilians’ Family, House and Life, containing curiosities of inestimable value, useful to rebuild not only the material and spiritual heritage left us by the alternation of historical dominations, but also to give back to the collective memory a wealth of experiences and costumes to illuminate our present. It is precisely in the second chapter, titled Nature and Personality of Sicilian People, that Pitrè described our magical expressive skills: “From the slightest, faintest vibration of the facial muscles to a whole movement of head and hands, this mute language expresses feelings, affections, will, which foreigners can’t understand. With gestures one affirms and denies, commands and obeys, arranges and executes, prays and blames, strokes and despise up to compose whole discourses”. The reference to the surprise aroused in the soul of foreigners, on the other hand, is far from specious. In the same chapter the ethnologist from Palermo told about one of the many travel reports prepared by the great European lords come to the island (Grand Tour must-visit) between the 18th and 19th centuries. Here’s what he wrote in a fun and emblematic page: “There are many travelers amazed by the island. In 1818 the count Fedor de Karaczay noticed that there was nothing fierier than the vitality of the Sicilian faces. A ripple of eyebrows, a way to stretch the chin, a way of contracting the nostrils, ‒ he said ‒ make an animated conversation with positive questions and answers. When the word then resumes its rights, the pantomime is so pressing, the fingers become so fast that the look can barely follow them”. As in every aspect of one’s existence, a Sicilian puts himself, with his own feelings and passions into play. The language is no exception.

Every quiver and rigidity of the whole body emphasize what we want to communicate, perhaps due to the need to shout our reasons for someone to listen to us over times, perhaps due to a way of understanding life devoted to expansiveness, or simply a link to our interlocutors. The fact is that the theatricality of the gesture is a part of our genetics and it’s no surprise it came to represent a common thread in the production of our great authors, from Verga and Pirandello’s characters to the performances by Turi Ferro and Angelo Musco. Life is a great stage and Sicilians, with their tragicomic masks, act with their unique confidence.

Translated by Daniela Marsala